Literature Review: The Intersection of Vulnerability and Supply Chain after Disaster in Puerto Rico

- Aisha Syed

- Oct 11, 2022

- 13 min read

Author: Aisha Syed

Advisor: Dr. Luis F. Rodríguez

Introduction

Puerto Rico has been hit with hurricanes with increasing frequency in recent years, the most memorable being Hurricane Maria in 2017. Hurricane Maria left the island in a 100% blackout, disrupting critical infrastructure (Aros-Vera et al., 2021). Additionally, the hurricane and the subsequent response caused multiple supply chain issues such as bottlenecking at ports, truck delivery disruptions, and fuel distribution problems (Crans, 2018). In addition to supply chain failures, there were disparities in how communities recovered (García-López, 2018; Ma & Smith, 2020), as is typical with areas affected by disasters.

Recovery item supply chains were already limited by the Jones Act, which requires that all vessels holding supplies that are shipped to Puerto Rico be US-made and operated (Valldejuli, 2016). The act was temporarily lifted, but not for long enough to make a significant impact on aiding supply chains (Kim & Bui, 2019). Supply chain failures in Puerto Rico were amplified by unproductive relief efforts (Martínez et al., 2020b). Such failures affected already strained supply chains at ports and roadways that disrupted food (Hecht et al., 2019; Orengo Serra & Sanchez-Jauregui, 2021), fuel (Martínez et al., 2020b; Eghbal Akhlaghi et al., 2021; Eghbal Akhlaghi & Campbell, 2022), construction (Arnerson, 2022), and medical (Kunkel, 2020; Lawrence et al., 2020b) supply chains that are essential to the recovery process. Additionally, disruptions caused prices to increase on the island due to limited item and labor supplies, and affected communities' abilities to recover (Anerson, 2022). There is a consensus that incorporating local actors are able to navigate such supply chain disruptions during the recovery process and are essential to disaster recovery (Kunkel, 2020; Carvalhaes et al., 2021; Sou, 2022).

Supply chain failures are informed by supply chain risks. Identified areas of supply chain risk are environmental risks. industry factors, organizational factors, problem-specific factors, and decision-maker-related factors (Rao & Goldsby, 2009). Variables within environmental risk include political uncertainty, policy uncertainty, macroeconomic uncertainty, social uncertainty, and natural uncertainty. Variables within industry risk include input market uncertainty, product-market uncertainty, and competitive uncertainty. Variables within organizational risk include operating uncertainty, liability uncertainty, credit uncertainty, and agency uncertainty. For this paper, environmental risks and therefore environmental failures are most relevant due to the relevant impacts on the consumer, and therefore the community.

Vulnerability is defined as “the characteristics of a person or group and their situation that influence their capacity to anticipate, cope with, resist and recover from the impact of a natural hazard (an extreme natural event or process)” (Wisner et al., 2004). Vulnerability characteristics can include individual characteristics, such as age, gender, health, occupation, caste, ethnicity, and disability (Wisner & Luce, 1993; Enarson, 1998; Wisner et al., 2004; Morris et al., 2018; Jerolleman, 2020; Rodríguez-Cruz et al., 2022), household characteristics (Enarson, 1998), economic conditions (Tarling, 2017; Talbot et al., 2020; Yabe et al., 2020) and geographic characteristics (Hunter & Arbona, 1995; Jerolleman, 2020).

The purpose of this literature review is to establish an understanding of the intersection between supply chain and vulnerability literature. In establishing a connection, our underlying hypothesis is that community vulnerability is associated with supply chain failures after a disaster. In order to prove the aforementioned underlying hypothesis, the following question must be answered: What are the characteristics of communities vulnerable to supply chain failures in Puerto Rico?

Materials and Methods

In order to understand which characteristics contribute to communities vulnerable to supply chain failures, I reviewed supply chain and vulnerability research in the context of disaster relief and recovery. I consulted ScienceDirect, Scopus, Google Scholar, and IEEE XPLORE using the keywords Vulnerability AND Supply Chain AND Disaster to guide my search. In total, I considered 57 articles, 38 of which will be discussed directly in this paper.

I started my search by reading papers discussing post-disaster supply chains, and identified vulnerability factors in such papers that were passively mentioned, but not directly discussed. After reviewing supply chain literature, I reviewed vulnerability literature in order to establish more connections that would be affected by supply chain failures.

Results

Given that supply chain failures affect communities’ ability to recover from a disaster and vulnerability includes the characteristics that affect a community’s ability to recover, it is reasonable to hypothesize there are characteristics that may affect a community’s ability to recover from supply chain failures after a disaster. In other words, supply chain failures may affect communities in different ways to different extents based on their vulnerability. The characteristics that influence vulnerability affected by failing supply chains from the literature can be categorized into the following categories: economic, political, environmental, and social.

Economic

Critical infrastructures, such as transportation, play a vital role in disaster relief because they impact how long it takes to recover after a disaster (Sathursan et al., 2022) and the coordination of supplying relief items to communities that need them (Kim & Bui, 2019; Martínez et al., 2020b; Tapia, 2020). Common transportation failures that interrupted disaster recovery efforts after Hurricane Maria include bottlenecking at ports and a lack of coordination between transportation agents and relief agencies (Kim & Bui, 2019; Martínez et al., 2020). Additionally, the further away from a port, the more road-related transportation errors may occur; this is given that transportation after a disaster is stochastic (Lawrence et al., 2020a), and different transportation times to different locations are affected by road conditions and obstacles (Kim & Bui, 2019; Resnick et al., 2020). Thus, factors that influence vulnerability are communities’ locations in relation to ports and roads.

Additional critical infrastructure that affects disaster recovery includes power, telecommunication, water supply, and hospital access (Sathursan et al., 2022). When critical infrastructure fails, disaster relief supply chains become vulnerable (Orengo Serra & Sanchez-Jauregui, 2021). Such failures impact community access to public services such as hospitals and make it more difficult for communities to recover after a disaster (Sou et al., 2021).

Broad economic vulnerability that is affected by supply chain failures is associated with factors such as operating manufacturing sites at a location, probability of economic collapse, and GDP (Martínez et al., 2020a) which affect available economic and financial resources (Orengo Serra & Sanchez-Jauregui, 2021). Community economic resources, labor markets associated with a community, and employment status are factors that impact recovery ability and community vulnerability as a result (Enarson, 1998; Wisner et al., 2004; Ingram et al., 2006; Kumar, 2017; Sou et al., 2021) A specific example of vulnerability as a result of financial disadvantages is the finding that lower-income and rental homes were more vulnerable to home damages in terms of monetary damages after Hurricane Maria (Ma & Smith, 2020).

Political

The connection between supply chain and politics is broadly recognized in the literature (Houshyar et al., 2010; Hecht et al., 2019; Tapia, 2020; Orengo Serra and Sanchez-Jauregui, 2021). Politics play a role in supply chain risks and vulnerabilities when political instability may be a source of uncertainty (Houshyar et al., 2010) or when government impact may provide uncertain impacts to disaster relief supply chains (Orengo Serra and Sanchez-Jauregui, 2021). Conversely, political affiliations were found to contribute to disaster relief supply chain resilience (Hecht et al., 2019). The consideration of the political impact on the capacity to rebuild is also prevalent in vulnerability literature (García-López, 2018; Morris et al., 2018; Jerolleman, 2020; Sou et al., 2021). Having political ties and therefore political power decreases vulnerability (Jerolleman, 2020), as those communities were found to have more access to disaster support and assistance (Sou et al., 2021).

Environmental

Environmental supply chain risks are related to the probability of natural disasters in the geographic area of interest (Martínez et al., 2020a). Disaster recovery disparities by region due to environmental factors also appear in vulnerability research when investigating recovery capabilities (García-López, 2018; Morris et al., 2018). Specific vulnerable environmental characteristics that are addressed include the lack of access to clean air and water (García-López, 2018; Morris et al., 2018).

Social

In this paper, social characteristics include demographic characteristics. The social factors apparent in supply chain literature are population size and community isolation (Palin et al., 2018). It was found that the more isolated and larger the population, the more dependent they are on private supply chains for relief materials. Therefore, large and isolated populations are more vulnerable than less isolated populations because they have limited access to relief materials. While large and isolated populations are more vulnerable, rural populations are more vulnerable than urban populations due to a lack of social capital and vulnerable ethnic make up (Jerolleman, 2020). Additionally, after Hurricane Maria, areas with a higher socioeconomic status and lower minority composition were prioritized in terms of power restoration (Tormos-Aponte et al., 2021); this suggests that vulnerability considerations include population, rural or urban classification, and social characteristics of the population.

Ethnicity is a common characteristic in vulnerability research (Wisner & Luce, 1993; Wisner et. al, 2004; García-López, 2018; Jerolleman, 2020). However, it should be noted that Puerto Rico has close to a uniform ethnic makeup (Tormos-Aponte et al., 2021), therefore ethnic differences are not as meaningful.

The most apparent social vulnerability characteristic addressed in vulnerability literature is age, as the elderly are more vulnerable (Wisner & Luce, 1993; Enarson, 1998; Wisner et. al, 2004; Ardalan et al., 2010) because age is related to health (Wisner & Luce, 1993; Wisner et. al, 2004; Ardalan et al., 2010). Older people are one of the most vulnerable during disaster times (Ardalan et al., 2010) because they are physically vulnerable. Physically vulnerable and disabled people are more vulnerable than healthy people (Wisner & Luce, 1993; Wisner et. al, 2004; Ardalan et al., 2010; Morris et al., 2018; Rodríguez-Cruz et al., 2022).

Additional social characteristics that increase vulnerability include household characteristics such as large families, divorce, and unemployment (Enarson, 1998).

Discussion

Overall, reviewing the literature allowed us to identify broad characteristics of communities vulnerable to supply chain failures in Puerto Rico. Specifically, communities that are vulnerable to supply chain failures are communities that don’t have easy access to roads, have failing and unreliable critical infrastructure, have a high unemployment rate, have little to no political impact, are environmentally vulnerable, and have a vulnerable demographic considering age, race, and health. Additionally, characteristics also have a geographic context in terms of rural vs urban communities, isolation, and proximity to ports and roads. Though there is a known geographic context, there is a gap in understanding how the aforementioned characteristics relate to each other on a geographic scale in Puerto Rico.

Economic factors, such as transportation, infrastructure, and economics play a role in supply chains by providing means of coordinating transportation and resources to support supply chain resilience. Economic factors also play a role in vulnerability in terms of lack of access to resources and vulnerable infrastructure. Communities with political power can create connections with relief agencies to gain access to more resources to aid in disaster recovery and expedite labor and relief items supply chains. However, those who are politically vulnerable are not prioritized in disaster relief efforts. Environmental considerations are apparent in vulnerability literature, and less apparent in supply chain literature. Environmental factors influence which roads will be damaged and therefore may cause interruptions in the transportation aspect of disaster recovery supply chains. Environmental factors determine how communities are vulnerable to natural disasters and other environmental risks. Social characteristics are most apparent in vulnerability literature but are rarely elaborated on in supply chain literature. However, social conditions may be extrapolated from supply chain literature. Social characteristics that impact community vulnerability are community characteristics such as population size, rural or urban classification, and population density, as well as personal characteristics such as age, household size, divorce status, and employment status.

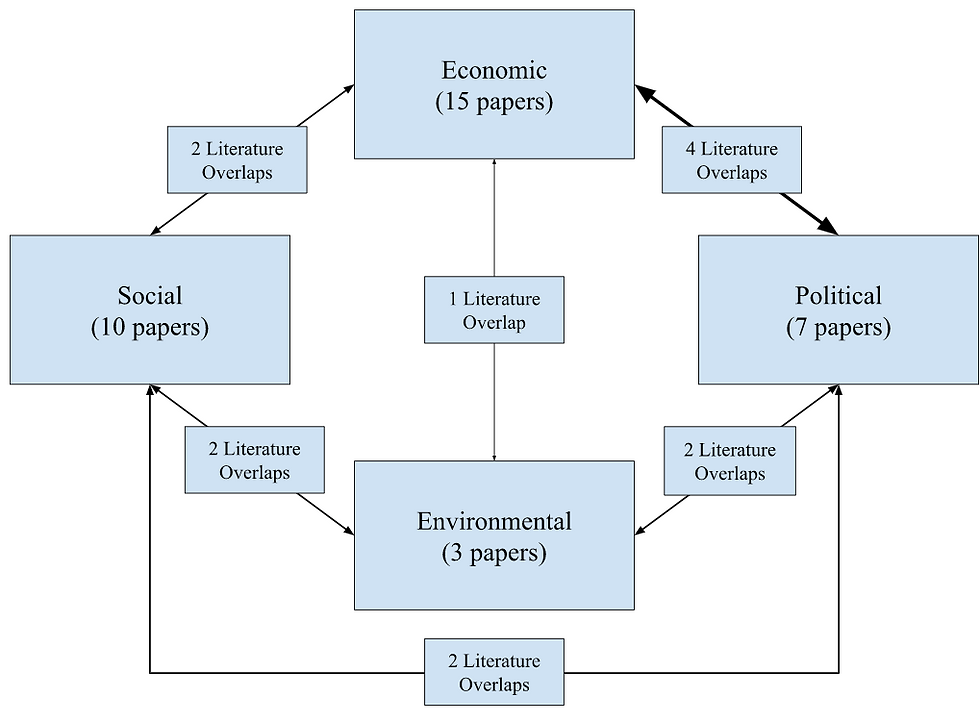

Overlaps in the literature include four papers common between Economic and Political, two papers common between Political and Environmental, one common paper between Economic and Environmental, two papers common between Political and Social, two papers common between Social and Environmental, and two papers common between Social and Economic (Figure 1). This shows that previous authors made connections between separate characteristics, most commonly Economic and Political, but there is a gap in connecting them all together in one paper.

Figure 1. Vulnerability Characteristics Literature Overlaps

Previous researchers have mainly used the following methods to investigate vulnerability characteristics: conducting interviews, creating models, risk analysis, vulnerability analysis, regression analysis, and content analysis. Geography was considered in a geographically informed risk regression analysis when evaluating environmental supply chain risk by global region (Martínez et al., 2020a) as well as regional discrepancies in power restoration priority given social vulnerability (Tormos-Aponte et al., 2021).

Based on previous research and methods, the identification of vulnerable populations that are prone to be most affected by supply chain failures that can be identified using geographic analysis techniques has not yet been resolved. Methods that inform how to test the hypothesis include mapping demographic characteristics, identifying population clusters, buffer analysis to identify communities that are close to ports and roads, environmental risk analysis using past hurricane data, and verifying the geographic analysis using needs and unmet needs from past Connect Relief data. I will use R to conduct geographic natural disaster risk analysis, and ArcGIS Pro to layer and visualize the vulnerability variables. Connect Relief, developed by Caras Con Causa and piloted in 2017 after Hurricane Maria, is a platform that allows aid receivers to communicate their needs directly to aid suppliers after a disaster. Data is collected via an app and published on a website. Past data is available in a database. Currently, Connect Relief is solely focused on Puerto Rican needs.

Conclusion

There is an intellectual understanding of the intersection of disaster relief supply chains and vulnerability because they are both concerned with communities recovering from a natural disaster. However, there is no explicit connection between vulnerability and disaster relief supply chains in the literature. Though connections are not specified, they can be extrapolated from supply chain and vulnerability literature to identify the characteristics of communities vulnerable to supply chain failures in Puerto Rico. We found that vulnerability factors that determine the impact of supply chain failures on a community include its economic, political, environmental, and social characteristics.

There is ample research about individual vulnerability and supply chain factors, but there is an absence of combining those related concepts using geographical analysis techniques. The refined hypothesis I will undertake in my research is: Vulnerable populations that are prone to be most affected by supply chain failures can be identified using geographic analysis techniques.

Previous researchers have used geographically informed risk analysis in their supply chain research. I would adapt their methods by analyzing the risks given geographical context in Puerto Rico aggregated by municipalities and extend beyond environmental and economic risks by also incorporating social and health risks that affect communities in Puerto Rico. The specific geographic analysis I plan to utilize is mapping demographic characteristics, identifying population clusters, buffer analysis to identify communities that are close to ports and roads, environmental risk analysis using past hurricane data, and verifying the geographic analysis using needs and unmet needs from past Connect Relief data.

Bibliography

Ardalan, A., Mazaheri, M., Naieni, K. H., Rezaie, M., Teimoori, F., & Pourmalek, F. (2010). Older people’s needs following major disasters: A qualitative study of Iranian elders’ experiences of the Bam earthquake. Ageing & Society, 30(1), 11–23. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0144686X09990122

Arneson, E. (2022). Disasters as Mega-Disruptions to Construction Supply Chains. 1-A, 551–559. Scopus. https://doi.org/10.1061/9780784483954.057

Aros-Vera, F., Gillian, S., Rehmar, A., & Rehmar, L. (2021). Increasing the resilience of critical infrastructure networks through the strategic location of microgrids: A case study of Hurricane Maria in Puerto Rico. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction, 55, 102055. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijdrr.2021.102055

Carvalhaes, T., Rinaldi, V., Goh, Z., Azad, S., Uribe, J., Chester, A., & Ghandehari, M. (2021). Integrating Spatial and Ethnographic Methods for Resilience Research: A Thick Mapping Approach for Hurricane Maria in Puerto Rico (SSRN Scholarly Paper No. 3863657). Social Science Research Network. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3863657

Crans, F. W. (2018). Embracing the principle of heroic intervention: Is that how Supply Chain really should plan for disruption? Healthcare Purchasing News, 42(7), 48–49.

Eghbal Akhlaghi, V., & Campbell, A. M. (2022). The two-echelon island fuel distribution problem. European Journal of Operational Research, 302(3), 999–1017. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejor.2022.01.030

Eghbal Akhlaghi, V., Campbell, A. M., & de Matta, R. E. (2021). Fuel distribution planning for disasters: Models and case study for Puerto Rico. Transportation Research Part E: Logistics and Transportation Review, 152, 102403. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tre.2021.102403

Enarson, E. (1998). The Gendered Terrain of Disaster: Through Women's Eyes, E. Enarson and B.H.Morrow, eds, 1998. https://www.academia.edu/943557/The_Gendered_Terrain_of_Disaster_Through_Womens_Eyes_E_Enarson_and_B_H_Morrow_eds_1998

García-López, G. A. (2018). The Multiple Layers of Environmental Injustice in Contexts of (Un)natural Disasters: The Case of Puerto Rico Post-Hurricane Maria. Environmental Justice, 11(3), 101.

Hecht, A. A., Biehl, E., Barnett, D. J., & Neff, R. A. (2019). Urban Food Supply Chain Resilience for Crises Threatening Food Security: A Qualitative Study. Journal of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics, 119(2), 211–224. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jand.2018.09.001

Houshyar, A. N., Muktar, M., & Sulaiman, R. (2010). Simulating the effect of supply chain risk and disruption: “A Malaysian case study.” 2010 International Symposium on Information Technology, 1362–1367. https://doi.org/10.1109/ITSIM.2010.5561636

Hunter, J. M., & Arbona, S. I. (1995). Paradise lost: An introduction to the geography of water pollution in Puerto Rico. Social Science & Medicine, 40(10), 1331–1355. https://doi.org/10.1016/0277-9536(94)00255-R

Ingram, J. C., Franco, G., Rio, C. R., & Khazai, B. (2006). Post-disaster recovery dilemmas: Challenges in balancing short-term and long-term needs for vulnerability reduction. Environmental Science & Policy, 9(7), 607–613. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envsci.2006.07.006

Jerolleman, A. (2020). Challenges of Post-Disaster Recovery in Rural Areas. In S. Laska (Ed.), Louisiana’s Response to Extreme Weather: A Coastal State’s Adaptation Challenges and Successes (pp. 285–310). Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-27205-0_11

Kim, K., & Bui, L. (2019). Learning from Hurricane Maria: Island ports and supply chain resilience. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction, 39, 101244. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijdrr.2019.101244

Kumar, K. (2017). Best Buy reopens store in Puerto Rico after months of helping employees recover. In Star Tribune (Minneapolis, MN) (Star Tribune (Minneapolis, MN)). Star Tribune (Minneapolis, MN). http://www.library.illinois.edu/proxy/go.php?url=https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=nfh&AN=2W63609326021&site=eds-live&scope=site

Kunkel, M. (2020). Lessons from a Hurricane: Supply Chain Resilience in a Disaster An Analysis of the US Disaster Response to Hurricane Maria. 55.

Lawrence, J.-M., Hossain, N. U. I., Rinaudo, C., & Jaradat, R. (2020a). An Approach to Improve Hurricane Disaster Logistics Using System Dynamics and Information Systems. Procedia Computer Science, 11.

Lawrence, J.-M., Ibne Hossain, N. U., Jaradat, R., & Hamilton, M. (2020b). Leveraging a Bayesian network approach to model and analyze supplier vulnerability to severe weather risk: A case study of the U.S. pharmaceutical supply chain following Hurricane Maria. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction, 49, 101607. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijdrr.2020.101607

Ma, C., & Smith, T. (2020). Vulnerability of Renters and Low-Income Households to Storm Damage: Evidence From Hurricane Maria in Puerto Rico. American Journal of Public Health, 110(2), 196–202. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2019.305438

Martínez, C., Paraskevas, J. P., Grimm, C., Corsi, T., & Boyson, S. (2020a). The Impact of Environmental Risks in Supply Chain Resilience. In H. Tsugunobu Yoshida Yoshizaki, C. Mejía Argueta, & M. Guimarães Mattos (Eds.), Supply Chain Management and Logistics in Emerging Markets (pp. 11–39). Emerald Publishing Limited. https://doi.org/10.1108/978-1-83909-331-920201002

Martínez, C., Paraskevas, J. P., Grimm, C., Corsi, T., & Boyson, S. (2020b). Resilience for whom? Demographic change and the redevelopment of the built environment in Puerto

Rico. In H. T. Y. Yoshizaki, C. Mejía Argueta, & M. G. Mattos (Eds.), Supply Chain Management and Logistics in Emerging Markets (pp. 11–39). Emerald Publishing Limited. https://doi.org/10.1108/978-1-83909-331-920201002

Morris, Z. A., Hayward, R. A., & Otero, Y. (2018). The Political Determinants of Disaster Risk: Assessing the Unfolding Aftermath of Hurricane Maria for People with Disabilities in Puerto Rico. Environmental Justice, 11(2), 89–94. https://doi.org/10.1089/env.2017.0043

Orengo Serra, K. L., & Sanchez-Jauregui, M. (2021). Food supply chain resilience model for critical infrastructure collapses due to natural disasters. British Food Journal, 124(13), 14–34. https://doi.org/10.1108/BFJ-11-2020-1066

Palin, P., Hanson, L., Barton, D., & Frohwein, A. (2018). Supply Chain Resilience and the 2017 Hurricane Season: A collection of case studies about Hurricanes Harvey, Irma, and Maria and their impact on supply chain resilience.

Rao, S., & Goldsby, T. J. (2009). Supply chain risks: A review and typology. International Journal of Logistics Management, 20(1), 97–123. https://doi.org/10.1108/09574090910954864

Resnick, A., DeCicco, A., Kilambi, V., Yoho, K., Vardavas, R., & Davenport, A. (2020). Logistics

Analysis of Puerto Rico: Will the Seaborne Supply Chain of Puerto Rico Support Hurricane Recovery Projects? RAND Corporation. https://doi.org/10.7249/RR3040

Rodríguez-Cruz, L. A., Álvarez-Berríos, N., & Niles, M. T. (2022). Social-ecological interactions in a disaster context: Puerto Rican farmer households’ food security after Hurricane Maria. Environmental Research Letters, 17(4), 044057. https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-9326/ac6004

Sathurshan, M., Saja, A., Thamboo, J., Haraguchi, M., & Navaratnam, S. (2022). Resilience of Critical Infrastructure Systems: A Systematic Literature Review of Measurement Frameworks. Infrastructures, 7(5), 67. https://doi.org/10.3390/infrastructures7050067

Sou, G. (2022). Reframing resilience as resistance: Situating disaster recovery within colonialism. The Geographical Journal, 188(1), 14–27. https://doi.org/10.1111/geoj.12413

Sou, G., Shaw, D., & Aponte-Gonzalez, F. (2021). A multidimensional framework for disaster recovery: Longitudinal qualitative evidence from Puerto Rican households. World Development, 144, 105489. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2021.105489

Talbot, J., Poleacovschi, C., & Hamideh, S. (2022). Socioeconomic Vulnerabilities and Housing Reconstruction in Puerto Rico After Hurricanes Irma and Maria. Natural Hazards, 110(3), 2113–2140. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11069-021-05027-7

Tapia, L. (2020). Best and Worst Resilience Practices Adopted by the Food and beverages

Supply Chain in the Aftermath of Natural disaster. 76.

Tarling, H. A. (2017). Comparative Analysis of Social Vulnerability Indices: CDC’s SVI and SoVI®. http://lup.lub.lu.se/student-papers/record/8928519

Tormos-Aponte, F., García-López, G., & Painter, M. A. (2021). Energy inequality and clientelism in the wake of disasters: From colorblind to affirmative power restoration. Energy Policy, 158, 112550. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2021.112550

Wisner, B., Blaikie, P., Cannon, T., & Davis, I. (2004). At Risk: Natural Hazards.

Wisner, B., & Luce, H. R. (1993). Disaster Vulnerability: Scale, Power and Daily Life. GeoJournal, 30(2), 127–140.

Yabe, T., Rao, P., & Ukkusuri, S. (2020). Regional differences in resilience of social and physical systems: Case study of Puerto Rico after Hurricane Maria. Environment and Planning B:

Urban Analytics and City Science, 48, 239980832098074. https://doi.org/10.1177/2399808320980744

.jpg)

Comments